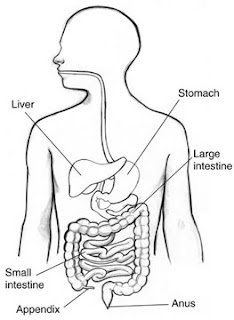

An inguinal hernia occurs when intra-abdominal fat or part of the small intestine bulges through a weak spot in the lower abdominal muscles. An inguinal hernia occurs in the groin—the area between the abdomen and thigh.

Inguinal hernia occurs more commonly in males than females and can occur any time from infancy to adulthood.

Types

There are two types of inguinal hernia: direct hernia and indirect hernia. These two types have different causes.

Indirect Inguinal Hernia

Indirect inguinal hernias are congenital hernias and are much more common in males than females because of the way males develop in the womb.

In a male fetus, the spermatic cord and both testicles—starting from an intra-abdominal location—normally descend through the inguinal canal into the scrotum, the sac that holds the testicles. Sometimes the entrance of the inguinal canal at the inguinal ring does not close as it should just after birth, leaving a weakness in the abdominal wall. Fat or part of the small intestine slides through the weakness into the inguinal canal, causing a hernia.

In a male fetus, the spermatic cord and both testicles—starting from an intra-abdominal location—normally descend through the inguinal canal into the scrotum, the sac that holds the testicles. Sometimes the entrance of the inguinal canal at the inguinal ring does not close as it should just after birth, leaving a weakness in the abdominal wall. Fat or part of the small intestine slides through the weakness into the inguinal canal, causing a hernia.

In females, an indirect inguinal hernia is caused by the female organs or the small intestine sliding into the groin through a weakness in the abdominal wall.

Indirect hernias are the most common type of inguinal hernia. Premature infants are especially at risk for indirect inguinal hernias because there is less time for the inguinal canal to close.

Direct inguinal hernia

Direct inguinal hernias are caused by connective tissue degeneration of the abdominal muscles, which causes weakening of the muscles during the adult years. Direct inguinal hernias occur only in males. The hernia involves fat or the small intestine sliding through the weak muscles into the groin. A direct hernia develops gradually because of continuous stress on the muscles. One or more of the following factors can cause pressure on the abdominal muscles and may worsen the hernia:

sudden twists, pulls, or muscle strainsIndirect and direct inguinal hernias usually slide back and forth spontaneously through the inguinal canal and can often be moved back into the abdomen with gentle massage.

lifting heavy objects

straining on the toilet because of constipation

weight gain

chronic coughing

Symptoms

Symptoms of an inguinal hernia usually appear gradually and include a bulge in the groin, discomfort or sharp pain, a feeling of weakness or pressure in the groin, and a burning, gurgling, or aching feeling at the bulge.

Incarcerated and Strangulated Inguinal Hernias

An incarcerated inguinal hernia is a hernia that becomes stuck in the groin or scrotum and cannot be massaged back into the abdomen.

A strangulated hernia, in which the blood supply to the incarcerated small intestine is jeopardized. This condition is serious, which requires immediate medical care. Symptoms include extreme tenderness and redness in the area of the bulge, sudden pain that worsens quickly, fever, rapid heart rate, nausea, and vomiting.

Diagnosis of Inguinal Hernia

To diagnose inguinal hernia, the doctor takes a thorough medical history and conducts a physical examination. The person may be asked to stand and cough so the doctor can feel the hernia as it moves into the groin or scrotum. The doctor checks to see if the hernia can be gently massaged back into its proper position in the abdomen.

Treatment of Inguinal Hernia

Inguinal hernias may be repaired through surgery. Surgery is performed through one incision or with a laparoscope and several small incisions.

Surgery for inguinal hernia is usually done on an outpatient basis. Recovery time varies depending on the size of the hernia, the technique used, and the age and health of the patient.

Complications

Complications from inguinal hernia surgery are rare and can include general anesthesia complications, hernia recurrence, bleeding, wound infection, painful scar, and injury to internal organs.

Suggested Readings:

View all Digestive Diseases Topics

Source: National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse (NDDIC), a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). NIH Publication No. 09–4634, December 2008

[Top of Page]